Remembering Aberfan

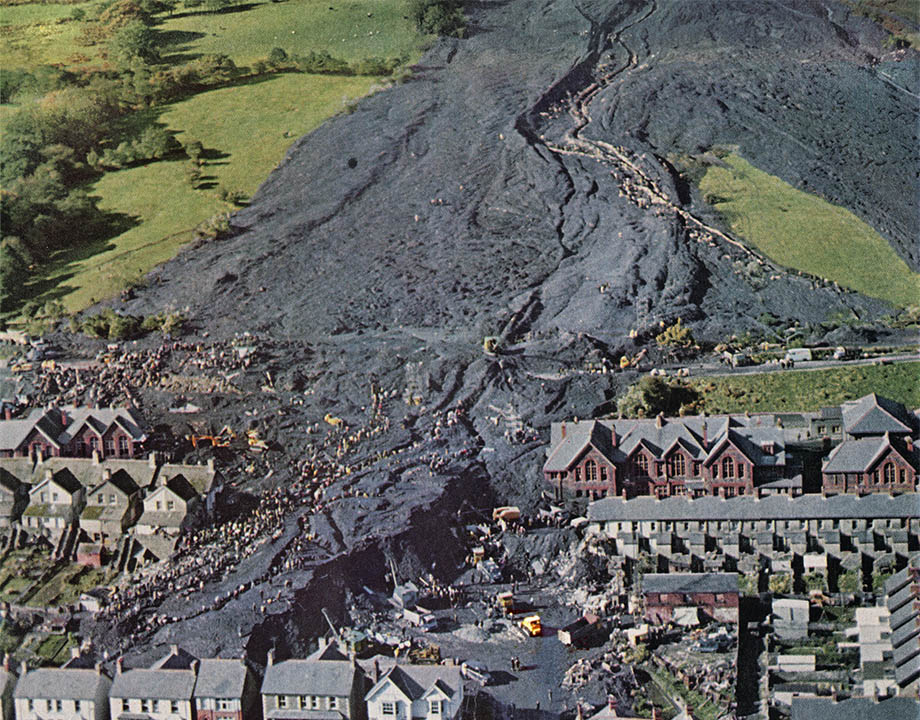

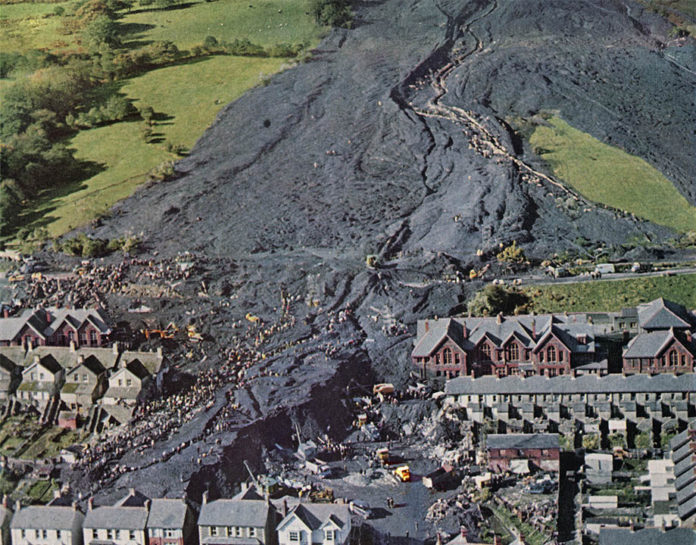

Early on the morning of Friday, 21 October 1966, after several days of heavy rain, a subsidence of approximately 10 – 20 feet (3–6 mtrs) occurred on the upper flank of colliery spoil heap No. 7. At 9.15 am more than 150,000 cubic metres (5,300,000 cu ft) of water-saturated debris broke away and flowed downhill at high speed. It was sunny on the mountain but foggy in the village, with visibility only about fifty metres (160 ft). The tipping gang working on the mountain saw the landslide start but were unable to raise the alarm because their telephone cable had been stolen. The official inquiry later established that the slip happened so fast that a telephone warning would not have saved any lives.

The front part of the mass became liquefied and moved down the slope at high speed as a series of viscous surges depositing 4,200,000 cubic feet (120,000 cu metres) of debris on the lower slopes of the mountain. A mass of more than 1,400,000 cubic feet (40,000 cu metres) of debris slid into the village in a slurry 40 feet (13m) deep.

The slide destroyed a farm and twenty terraced houses along Moy Road and struck the northern side of Pantglas Junior School and part of the separate senior school, demolishing most of the structures and filling the classrooms with thick mud, sludge and rubble up to 30 foot (10 metres) depth. Mud and water from the slide flooded many other houses in the vicinity, forcing many villagers to evacuate their homes.

The pupils of Pantglas Junior School had arrived only minutes earlier for the last day before the half-term holiday. The teachers had just begun to record the children’s attendance in the registers when a great noise was heard outside. They were in their classrooms when the landslide hit; the classrooms were on the side of the building nearest the landslide.

Nobody in the village could see it, but everyone heard the roar of the approaching landslide. Some at the school thought a jet plane was about to crash and one teacher ordered his class to hide under their desks. Gaynor Minett, an eight-year-old at the school, later recalled:

It was a tremendous rumbling sound and all the school went dead. You could hear a pin drop. Everyone just froze in their seats. I just managed to get up and I reached the end of my desk when the sound got louder and nearer, until I could see the black out of the window. I can’t remember any more but I woke up to find that a horrible nightmare had just begun in front of my eyes.

After the landslide there was total silence. George Williams, who was trapped in the wreckage, remembered:

In that silence you couldn’t hear a bird or a child.

After the main landslide stopped, frantic parents rushed to the scene and began digging through the rubble, some clawing at the debris with their bare hands, trying to uncover buried children. Police from Merthyr Tydfil arrived soon after and took charge of the search-and-rescue operations. As news spread, hundreds of people drove to Aberfan to try to help, but their efforts were largely in vain. Water and mud was still flowing down the slope, and the growing crowd of untrained volunteers hampered the work of trained rescue teams who were arriving. Hundreds of miners from local collieries rushed to Aberfan, especially from Merthyr Vale Colliery. Miners arrived from Deep Navigation and Taff Merthyr Collieries in the neighbouring Taff Bargoed Valley. More men came from pits across the South Wales coalfield, many in open lorries with shovels in their hands, but by the time they reached Aberfan there was little they could do. A further threat was posed by a fresh torrent of water, released by two water mains, supplying the city of Cardiff, which had been fractured by the avalanche breaking through the old railway line embankment. The additional water flooded into the already saturated mounds of slurry. The flow of water was eventually stopped at 11.30 am.

A few children were pulled out alive in the first hour, but no survivors were found after 11 am.

By the next day, 2,000 emergency services workers and volunteers were on the scene, some of whom had worked continuously for more than 24 hours. Rescue work was temporarily halted when water began pouring down the slope again. Because of the vast quantity and consistency of the spoil, it was nearly a week before all the bodies were recovered.

Bethania Chapel, 273 yards (250 m) from the disaster site, became a temporary mortuary and missing persons bureau from 21 October until 4 November 1966 and its vestry was used by Red Cross volunteers and St John Ambulance stretcher-bearers. The smaller Aberfan Calvinistic Chapel was used as a second mortuary from 22–29 October and was “the final resting-place for the deceased before internment.”

Two doctors examined the bodies and issued death certificates; the causes of death were typically asphyxia, fractured skull or multiple crush injuries. A team of 400 embalmers arrived on Sunday and under police supervision cleaned and prepared more than 100 bodies and placed them in coffins obtained from South Wales, the Midlands, Bristol and Northern Ireland. The bodies were released to the families from the morning of Monday 24 October. Cramped conditions in the chapel meant that parents could only be admitted one at a time to identify the bodies of their children. One mother recalled being shown the bodies of almost every dead girl recovered from the school before identifying her own daughter.

The death toll was 144, among the dead were five teachers and 116 children between the ages of 7 and 10, almost half the children on role at Pantglas Junior School. Most victims were interred at Bryntaf Cemetery in Aberfan in a joint funeral on 27 October 1966, attended by more than 2,000 people.

wikipedia.org

Take a moment to reflect and spare a thought for a town’s generation NOT to be forgotten.