FLIPPING through a collection of pre-war photographs I was struck by changes that have since taken place.

About 1925, a young man named Billy Butlin took a break and stayed at a Bed and Breakfast in Barry Island, Wales.

Standard practice was that guests would be locked out of their accommodation after breakfast and allowed back in only when it suited the householder.

Uninspired by such indifference Butlin decided to create a new kind of holiday, one where residents wouldn’t be subject to petty restrictions and encouraged to come and go as they pleased.

His thoughts turned to camping holidays but in chalets rather than under canvas. Free entertainment would be provided for the guests between meals.

Instead of their having to kill time before being allowed back into their accommodation, all the guests had to think about was which activity they wanted to do next.

Butlin, a 25-year old South African envisaged a holiday utopia but little realised it would become a mainstay of the British seaside for generations.

Attracted to innovation and social progress Billy Butlin worked his way up from working at a travelling fair to owning a travelling fair.

Through hard work he opened a permanent fairground in Skegness in 1927, becoming the first person to bring dodgems into Britain.

The site even included a zoo. He opened his first Butlin’s Holiday Camp in 1936, close to Skegness.

On the opening night, an engineer was asked to break the ice with paying guests by cracking jokes and telling stories.

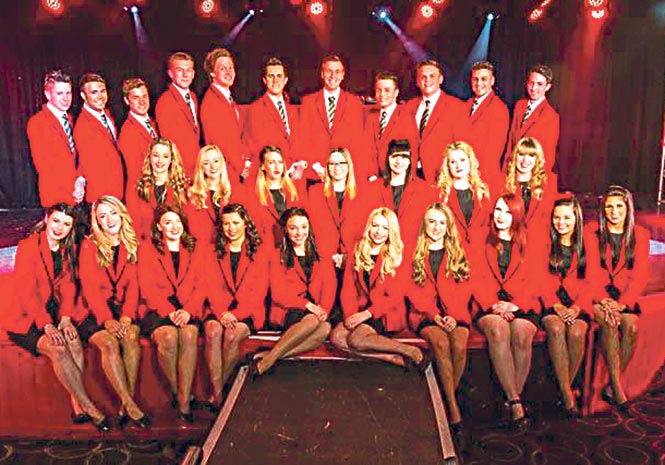

The guests loved it, and thus, an institution of British entertainment was born; the Butlin’s Redcoat, whose responsibility it was to keep the guests entertained.

Since then, famous Redcoats have included Des O’Connor, Jimmy Tarbuck, Ted Rogers, Sir Cliff Richard and Rod Hull.

Butlin opened camps in Clacton-on-Sea and Dovercourt in quick succession. In 1938, a year before the outbreak of the Second World War, the later was confiscated by the government to house the children who came to England as part of the Kinder Transport.

Clacton and Skegness camps were seized for training camps for troops. Such was the government’s rate of conscription that Butlin built more camps on the promise they would be returned to him following the war.

When the camps were returned to him Butlin’s voracious appetite for expansion continued. He opened camps in Ayr, Saltdean, Blackpool, and Cliftonville and even on the island of Grand Bahama.

These camps were followed by new openings in Bognor Regis, Minehead and the very place that created this holiday behemoth, Barry Island.

Despite cheap air flights Butlin’s dream is still the dream holiday for many Britons.